The Egyptian Orthodox Christian community—the Copts—has been the target of violence and discrimination since the 1970s and especially following the revolution that overthrew Hosni Mubarak. The Egyptian state has done little to remedy the situation and has at times enabled the conflict between Muslims and Christians. Achieving religious freedom and equality depends on building state institutions that can guarantee all citizens’ constitutional rights.

The Conflict

Regime-church relations deteriorated in the 1970s under President Anwar Sadat, who embraced Islam and Islamists as a counterweight to the left.

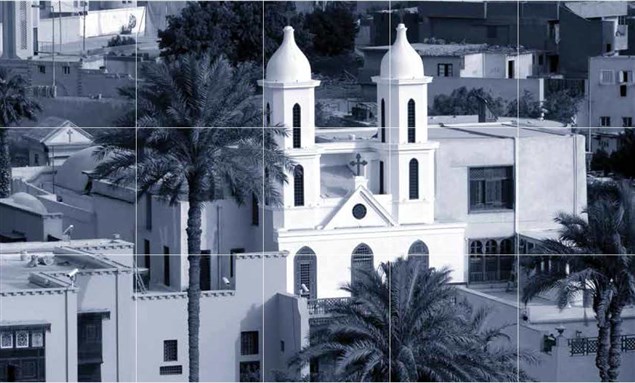

Churches are flash points for anti-Coptic attacks. The construction and renovation of churches is a highly political process in Egypt that has historically required presidential approval to proceed.

When Copts are physically attacked, the army and police frequently do not intervene to ensure public safety, enabling the spread of assaults. On occasion, such as an incident at the Egyptian Radio and Television Union (Maspero) in October 2011, security personnel have even used lethal violence against unarmed Copts.

While attacks by Muslims on Copts have a sectarian element, confessional differences are not the primary source of tension. Egypt’s outdated laws and authoritarian institutions have made Copts a target of social conflict.

Recommendations for the Egyptian Government

Broaden the political transition process to include a wider range of participants. Appointment of Coptic elites to ministerial posts or to the subset of unelected parliamentary seats may strengthen the voice of Christians in government and remedy institutional shortcomings. But this does not do away with the need to address inequality in the rest of the country.

Undertake security reforms that put police in the service of local communities. A relic of authoritarian rule, the police currently serve the Egyptian state instead of the Egyptian people. Police should protect all Egyptian citizens, including the Copts, not just the interests of the state.

Investigate the failure of security forces to defend churches and other sites targeted because of their connection to Coptic communities. Prosecution of assailants and broader policy changes must be informed by a careful evaluation of recent events, including the negligence of security officials at all levels to provide basic security for Egyptian citizens of all faiths.

Revisit the recommendations of the al-Utayfi Committee’s report. Released after a wave of sectarian clashes in 1971–1972, the report recommended that the government clarify procedures for church construction. Passing a unified law on construction of houses of worship and enforcing it can help alleviate a recurrent source of conflict.

Introduction

The demise of Egypt’s elected Islamist government in July has not delivered a hopeful beginning for interfaith relations. Violence was rising in Egypt even before the military deposed President Mohamed Morsi in a coup embraced by millions, but social and political turmoil has only escalated since then. The killings by Egyptian security forces of upwards of 1,000 Morsi supporters in separate mass shootings in July and August have been the most notorious incidents. Lethal attacks on Egyptian Christians, Copts, are also cause for alarm. Assailants from the northern Sinai to southern Egypt have besieged churches and slain Coptic clergy and laypersons. This trend escalated after police violently cleared the main pro-Morsi protests in Cairo on August 14.1

A rash of hate crimes seldom bodes well. Now, during Egypt’s second military-led transitional government in as many years, sectarian tension harkens back to the state indifference and social angst that fueled the original Egyptian Revolution of January 25, 2011. Human rights organizations have linked some attacks against Copts to partisans of the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist organizations. They have also reported that the military and police have often made a bad situation worse, by ignoring calls for help and letting the perpetrators rampage freely. Their criticism reveals how Coptic security is tied to the broader effort to establish a government that treats Egyptians as citizens with rights rather than a problem to be managed.

The question of citizenship—full membership in the national political community—has bedeviled all Egyptians, whether they practice Islam, Christianity, Judaism, or another faith. The country officially became a republic in 1953, but state officials never became truly accountable to the public they ostensibly served. To take one particularly egregious example, the police have been as likely to prey upon Egyptians as to protect them. Hosni Mubarak’s longest-serving minister of the interior went so far as to replace his department’s slogan, “the police in the service of the people,” with “the police and the people in the service of the nation.”2 In practice, the ministry’s extortion schemes effectively put the people in the service of the police. In June 2010, when young entrepreneur Khaled Said threatened to expose police involvement in trafficking, two police officers in Alexandria hauled the young man from an Alexandria cybercafé and beat him to death. Said’s killing, immortalized in the “We Are All Khaled Said” Facebook group, became a cause célèbre. Notably, the Ministry of the Interior from which Said’s killers hailed has been one of the most criticized and least changed institutions of the ongoing transition.

For sixty years Egyptian leaders have defended a rigid hierarchy instead of instituting political equality. The country’s military rulers shared power with only a few civilians. The rest of the population, numbering in the tens of millions, got by on whatever rights and opportunities the regime bestowed. Under such an authoritarian system, religious identity mattered less than wealth and personal connections to the army. It follows that most Egyptians, Muslims and Copts alike, have experienced a kind of second-class citizenship when interacting with their government.

What, then, has religion got to do with it? In a country that played an integral role in the global spread of Christianity and Islam, religion has served to fragment a society that is already sharply split between rulers and ruled. The regime of President Anwar Sadat grew more overtly pious in the 1970s, inserting the call to prayer into national television programs and banning the sale of alcohol in much of the country.3 Copts found Egypt being defined in terms that excluded them from belonging in equal measure alongside Muslim Egyptians.

The problem of sectarianism persisted. Aside from a moment of intercommunal harmony during the eighteen-day uprising against Hosni Mubarak, Copts have faced discrimination and oppression under the former authoritarian regime and the transitional governments that followed it: the army’s massacre of civilians at Maspero in October 2011; the siege on St. Mark’s Cathedral in April 2013 near the end of Mohamed Morsi’s presidency; the shootings, beheadings, and church burnings that General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi’s forces did little prevent after el-Sisi took power in July. In sum, Copts remain one of Egyptian society’s most vulnerable communities.

Anti-Coptic violence during the past forty years emerged from the intersection of religious discourse and authoritarian control. Sadat promoted Islam in public life and rebuilt the Nasserist police state as a means of shoring up his political position. Coptic complaints about Morsi, which grew during his twelve-month tenure, are rightly seen in this light: the rise of the Muslim Brotherhood and allied conservative Islamists exposed the Copts’ political predicament, a predicament that had been produced by the old regime. Thus, the end of Egypt’s first Islamist presidency does not presage a golden age for Muslim-Coptic relations, but merely a return to the subtler, pernicious problems of the Sadat-Mubarak era.

Violence against Egypt’s Coptic community, the largest population of Christians in the Middle East, must be viewed in its historical and institutional context. Any attack by Muslims on Copts carries a sectarian element, but it is Egypt’s outdated laws and authoritarian institutions, not confessional differences, that have made Copts a target of social conflict.

Aside from physical assaults, Copts face numerous forms of quotidian discrimination. Copts have been customarily barred from positions of leadership (including university presidencies and governorships, with a few exceptions discussed below) as well as positions deemed sensitive to national security, from the upper echelons of the security apparatus to the pedagogical front lines where Copts are prevented from teaching Arabic. Everyday forms of prejudice no doubt contribute to a climate of insecurity. Institutional changes will not be sufficient to bring about a shift in social attitudes, but state officials can build an environment where such shifts are much more likely to take place.

Today, a lack of political will and institutional reform helps explain why President Morsi’s downfall has not made Copts feel safer. With respect to the law, when Copts want to construct or renovate their places of worship, an essential practice for freedom of belief and religious equality, they face a political minefield rather than a simple administrative process. Next, in terms of public safety, the Ministry of Defense and Ministry of Interior, Egypt’s chief security institutions, have not altered the modus operandi they acquired under the Free Officers regime more than a half century ago. In the main, police and soldiers behave as if their first duty was to Egypt’s political leaders, not its people, and when violence has erupted they have been absent or complicit. These flaws—as well as the broader phenomenon of anti-Coptic discrimination in everyday affairs—weigh heavily on current discussions of a “road map” to a stronger and more egalitarian Egypt. If the current cohort of leaders—officers and civilians—wishes to protect and include all Egyptians, it will need to enact the legal and security reforms that Sadat, Mubarak, Mohamed Hussein Tantawi (the armed forces commander who was de facto head of state after Mubarak’s ouster), and Morsi failed to undertake. Such efforts could help rebuild a national sense of “Egyptianness” that has waned under secular and Islamist rulers alike.

[The above text is reprinted by permission of the publisher from “Violence Against Copts in Egypt,” Jason Brownlee (Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2013) pp. 1–2, www.carnegieendowment.org/. Click here to download the full working paper.]